Mo Rahma – The UAE’s first competitive surfer pulling in to a clean one at Wadi Adventure Wave Pool in Al Ain, UAE.

Originally published on StabMag.com on March 25, 2015 as Meet Surfing’s First Chlorine Creation!

Story by: Lucas Townsend

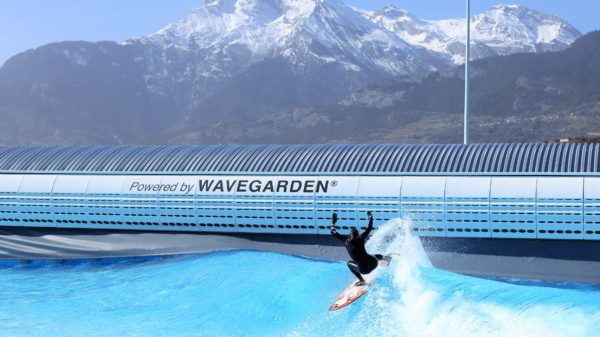

Mo Rahma pays $10 for every wave he surfs. Twice a month he drives an hour and a half from his home in Dubai to the Wadi Wavepool in Al-Ain. Although oil rich, gas is not free in this land and he’ll fill the tank of his Tundra pick-up truck for $30. He’ll pay another $30 to enter the facility, and $60 for an hour session in the pool. To make the trip worthwhile, he’ll surf for three hours. $180. There’s no more than six people, and the wave comes every two minutes. He can only catch six waves, and every time he falls, $10 is wasted. He will never paddle more than 20 metres, and he will never have to duck-dive.

Mo is the first surfer of the wavepool generation and he’s hacked at the 100k salary he earns as a sales and development manager for Etihad Airways learning to surf. Like much of Dubai, if locals want something bad enough they’ll throw down the cash to make it happen. And Mo wants to be a professional surfer.

In October, World Surfing League’s awkward cousin, the International Surfing Association (ISA), held its World Surfing Games at Punta Rocas in Peru. And just as awkward cousins do, the ISA seemingly let anyone come to family lunch. It’s not cruel, only truthful, to say they’re more about inclusion than groundbreaking surfing. Mo, representing the UAE, would struggle to make first round heats against kids on the junior series in Oz. And I write that with no disrespect. “Four years ago I never knew what surfing was,” says Mo. “I didn’t know what a surfboard looked like. We get wind swell in Dubai rarely, but it’s ankle high. I was pushed into my first wave on a SUP… eight months later they opened the wavepool and that’s when I went and tried it properly. I’ve been surfing in the pool ever since.”

“As soon as I hear the voice, I paddle.” The voice cues the wave.

Mo takes two, sometimes three strokes, then gets to his feet. He stalls, cuts back until the wave stands, then fits two turns in before the wave’s over. The only variable is wind, strong enough in the desert to pick up a board and hurl it into the walls. Mo ruins six boards a year this way, or they’ll be damaged on the cement floor of the pool. Surfing, for Mo, looked like this for two years. He’d never understood an ocean, or been stung by lice, or felt a current pull him towards rocks or even had sand stuck in his wax. Up until that point, surfing in the wavepool was a sport not too dissimilar to football or rugby. He’s represented his country in both, but a knee injury ended it all and running in the ocean was rehab. There he saw surfing for the first time and decided the pool was his gateway to competitive surfing.

“The first time I went in the ocean was in Sri Lanka. I saw 20 people surfing to the left, and 10 people surfing to the right, and no one surfing in the middle. I was like, I’m going to paddle out right in there. I grabbed my board and paddled out and the taste of salt water was horrible! My fins kept smashing on the coral and I was worried, but I thought, maybe this is normal. I didn’t know what coral was, so I kept paddling and my fins got fucked up. I caught my first wave and it was hollow so I didn’t make it. I wiped out, cut myself and I was like, fuck, what just happened to me? I got back to the hotel and everyone was like, ‘Ah, it’s a sea urchin.’ What the fuck is a sea urchin? My feet were all black. I had to go straight to the doctor to get the 30 spines out – and that was my first time in the ocean.”

Ignorance isn’t bliss all the time. Mo is the litmus test for landlocked wavepools, showing pool surfing cannot be translated into surfing surfing. Rugby or football training is about simulation. Recreating moments from a game with the intention to perfect, and then replicate during the next match. Like an empty field with witches hats, wavepools act on the same principle: “When you get the same wave every single time it’s just muscle memory. It got boring.”

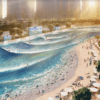

Since the 60’s we’ve been tormented by the promises of waves in a chlorinated wonderland. Millions of dollars have circled the drain to make the first fully functional, and impressive wavepool. So much of surfing looks backwards, but quality artificial waves have owned conversations about the future, more than board design and product technology, because we know exactly what we want, we’ve just never had it. The Wavegarden in Spain’s Basque Country and the Wadi Adventure Wavepool have come closest to Shangri-La but logistics and legalities have held back bigger projects. Purists still ask their question of, why? And every marketer’s response is: “We’re revolutionising surfing participation, bringing the coast to the metropolis… surfing is now for everyone.” And Mo, who pulled on a jersey for the first time in Peru, discovered surfing, artificially. And paid for it.

Sally Fitz on a $10 wave at Wadi Adventure wave pool in Al Ain, UAE. Photo: Trent Mitchell / Red Bull

Two years after Dion Agius and Joe G took two Lamborghinis and 10 Russian models to the aqua blue for Stab, the Al-Ain desert city now offers a peculiar look to the future of what wavepools have really created, and what they’ll undoubtedly create more of: Pool-bred surfers. But what it did for Mo was invite the need to find real surfing in a real ocean, a different kind of Shangri-La, one that we’ve had the entire time. “I meet people around surfing and I wonder, why are you so grumpy? You’re a surfer, you should be stoked all the time. When I got pushed on my first wave, I realised I’d wasted my whole childhood not surfing. That was the best moment of my life. Then, dropping into an eight-foot wave in Peru, that replaced it. The smile on my face, it was like I was doing a commercial for toothpaste.” We’re transfixed on the pathway to riding artificial waves. But when a product of that very place walks towards us, desperate to know where we’ve come from, perhaps it’s time to stop, turn around and show him it isn’t all that bad.

Dion Agius pulling into a closeout barrel at Wadi Adventure Wave Pool during Globe’s shoot for Electric Blue Heaven

You must be logged in to post a comment Login